Transaction

We believe it is better to have application programmers deal with performance

problems due to overuse of transactions as bottlenecks arise, rather than

always coding around the lack of transactions.

— James Corbett et al., Spanner: Google’s Globally-Distributed Database (2012)The Slippery Concept of a Transaction

The Meaning of ACID

ACID: Atomicity + Consistency + Isolation + Durability

Atomicity: In an atomic transaction, if the transaction cannot be completed (committed) due to a fault, then the transaction is aborted and the database must discard or undo any writes it has made so far in that transaction.Consistency: You have certain statements about your data (invariants) that must always be true. This is not something that the database can guarantee: Atomicity, isolation, and durability are properties of the database, whereas consistency (in the ACID sense) is a property of the application.Isolation: Isolation in the sense of ACID means that concurrently executing transactions are isolated from each other: they cannot step on each other’s toes.Serializability: The classic database textbooks formalize isolation as serializability, which means that each transaction can pretend that it is the only transaction running on the entire database.

Durability: The promise that once a transaction has committed successfully, any data it has written will not be forgotten, even if there is a hardware fault or the database crashes.

Weak Isolation Levels

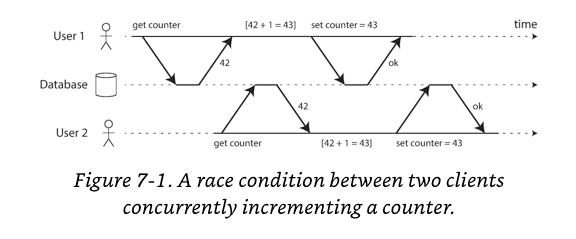

Concurrency bugs are hard to find by testing, because such bugs are only triggered when you get unlucky with the timing. Such timing issues might occur very rarely, and are usually difficult to reproduce. Concurrency is also very difficult to reason about, especially in a large application where you don’t necessarily know which other pieces of code are accessing the database. Concurrency issues (race conditions) only come into play when one transaction reads data that is concurrently modified by another transaction, or when two transactions try to simultaneously modify the same data.

Read Committed

Read Committed is the most basic level of transaction isolation.

Read Committed guarantees:

- When reading from the database, you will only see data that has been committed (no dirty reads).

- When writing to the database, you will only overwrite data that has been committed (no dirty writes).

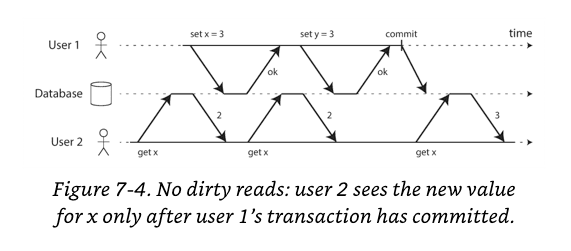

No Dirty Reads

Dirty Read: Another transaction seeing uncommitted data.

Why is preventing dirty reads useful?

- If a transaction needs to update several objects, a dirty read means that another transaction may see some of the updates but not others. Seeing the database in a partially updated state is confusing to users and may cause other transactions to take incorrect decisions.

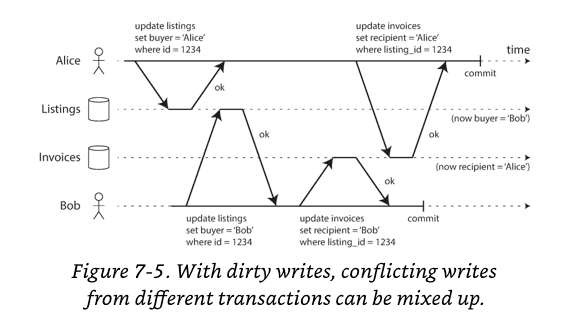

No Dirty Writes

Dirty Write: If the earlier write is part of a transaction that has not yet committed, and therefore later write overwrites an uncommitted value?

Why is preventing dirty writes useful?

- If transactions update multiple objects, dirty writes can lead to a bad outcome.

- For example, let's say two people, Alice and Bob are trying to buy the same car. Buying a car requires two database writes: the listing on the website needs to be updated to reflect the buyer, and the sales invoice needs to be sent to the buyer. In the case of Figure 7-5, the sale is awarded to Bob (because he performs the winning update to the listings table), but the invoice is sent to Alice (because she performs the winning update to the invoices table). Read committed prevents such mishaps.

- For example, let's say two people, Alice and Bob are trying to buy the same car. Buying a car requires two database writes: the listing on the website needs to be updated to reflect the buyer, and the sales invoice needs to be sent to the buyer. In the case of Figure 7-5, the sale is awarded to Bob (because he performs the winning update to the listings table), but the invoice is sent to Alice (because she performs the winning update to the invoices table). Read committed prevents such mishaps.

Implementing Read Committed

Read Committed is a very popular isolation level: default setting in Oracle11g, PostgreSQL, SQL Server 2012, MemSQL, etc.

Most commonly, databases prevent dirty writes by using row-level locks: when a transaction wants to modify a particular object (row or document), it must first acquire a lock on that object. How do we prevent dirty reads? One option would be to use the same lock, and to require any transaction that wants to read an object to briefly acquire the lock and then release it again immediately after reading.

However, the approach of requiring read locks does not work well in practice, because one long-running write transaction can force many other transactions to wait until the long-running transaction has completed, even if the other transactions only read and do not write anything to the database. Most databases prevent dirty reads using the following approach: for every object that is written, the database remembers both the old committed value and the new value set by the transaction that currently holds the write lock. While the transaction is ongoing, any other transactions that read the object are simply given the old value.

Snapshot Isolation and Repeatable Read

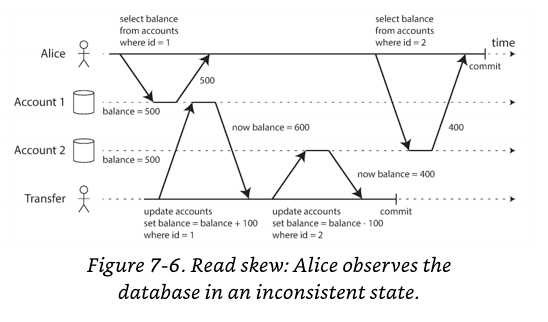

There are limitations of Read Committed isolation level. One example is a read skew, explained below.

In the above example, if Alice is unlucky enough to look at her list of account balances in the same moment that the transaction is being processed, she may see that her account only has a total of $900.

This anomaly is called read skew, and it is an example of a nonrepeatable read: if Alice were to reload the online banking website, she would see a total of $1000 in her deposit.

However, there are some situations that cannot tolerate such read skew.

Backups: Taking a backup requires making a copy of the entire database, which may take hours on a large database. During the time that the backup process is running, writes will continue to be made to the database. Thus, you could end up with some parts of the backup containing an older version of the data, and other parts containing a newer version. If you need to restore from such a backup, the inconsistencies (such as disappearing money) become permanent.Analytics query and integrity checks: These queries are likely to return nonsensical results if they observe parts of the database at different points in time.

Snapshot Isolation is the most common solution to this problem. The idea is that each transaction reads from a consistent snapshot of the database—that is, the transaction sees all the data that was committed in the database at the start of the transaction.

Snapshot isolation is useful for long-running, read-only queries such as backups and analytics. In essence, snapshot isolation is a useful isolation level, especially for read-only transactions.

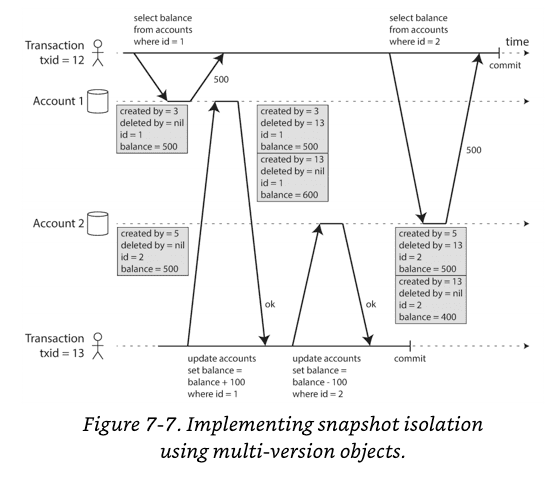

Implementing Snapshot Isolation

Implementations of snapshot isolation typically use write locks to prevent dirty writes, but reads do not require any locks. A key principle of snapshot isolation is readers never block writers, and writers never block readers.

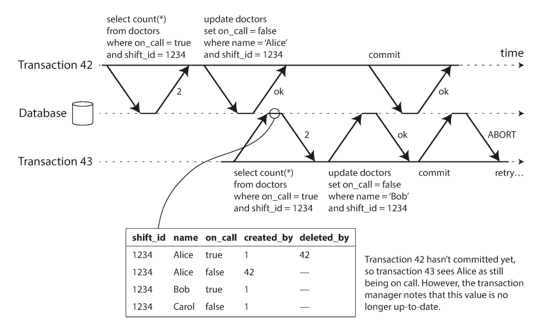

Multi-version concurrency control (MVCC): The database must potentially keep several different committed versions of an object, because various in-progress transactions may need to see the state of the database at different points in time.

Each row in a table has a created_by field, containing the ID of the transaction that inserted this row into the table. Moreover, each row has a deleted_by field, which is initially empty.

Indexes and Snapshot Isolation

How do indexes work in a multi-version database?

PostgreSQL has optimizations for avoiding index updates if different versions of the same object can fit on the same page

CouchDB, Datomic, and LMDB use append-only/copy-on-write variant that does not overwrite pages of the tree when they are updated, but instead creates a new copy of each modified page.

Preventing Lost Update

Other than dirty writes, there are several other interesting kinds of conflicts that can occur between concurrently writing transactions.

The best known of these is the lost update problem, with the example of two concurrent counter increments.

The lost update problem can occur if an application reads some value from the database, modifies it, and writes back the modified value (read-modify-write cycle). If two transactions do this concurrently, one of the modifications can be lost, because the second write does not include the first modification.

Because this is such a common problem, a variety of solutions have been developed.

Atomic write operations

Many databases provide atomic update operations, which remove the need to implement read-modify-write cycles in application code. For example, the following instruction is concurrency-safe in most relational databases:

UPDATE counters SET value = value + 1 WHERE key = 'foo';Unfortunately, object-relational mapping frameworks make it easy to accidentally write code that performs unsafe read-modify-write cycles instead of using atomic operations provided by the database

Explicit locking

Application explicitly locks objects that are going to be updated. Then the application can perform a read-modify-write cycle, and if any other transaction tries to concurrently read the same object, it is forced to wait until the first read-modify-write cycle has completed.

For example, consider a multiplayer game in which several players can move the same figure concurrently. In this case, an atomic operation may not be sufficient, because the application also needs to ensure that a player’s move abides by the rules of the game, which involves some logic that you cannot sensibly implement as a database query.

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

SELECT * FROM figures

WHERE name = 'robot' AND game_id = 222

FOR UPDATE;

-- The FOR UPDATE clause indicates that the database should take a lock on all rows returned by this query.

-- Check whether move is valid, then update the position

-- of the piece that was returned by the previous SELECT.

UPDATE figures SET position = 'c4' WHERE id = 1234;

COMMIT;Automatically detecting lost updates

An alternative is to allow them to execute in parallel and, if the transaction manager detects a lost update, abort the transaction and force it to retry its read-modify-write cycle.

An advantage of this approach is that databases can perform this check efficiently in conjunction with snapshot isolation. Indeed, PostgreSQL’s repeatable read, Oracle’s serializable, and SQL Server’s snapshot isolation levels automatically detect when a lost update has occurred and abort the offending transaction. However, MySQL/InnoDB’s repeatable read does not detect lost updates

Compare-and-set

In databases that don’t provide transactions, you sometimes find an atomic compare-and-set operation. The purpose of this operation is to avoid lost updates by allowing an update to happen only if the value has not changed since you last read it. If the current value does not match what you previously read, the update has no effect, and the read-modify-write cycle must be retried.

-- This may or may not be safe, depending on the database implementation

UPDATE wiki_pages SET content = 'new content'

WHERE id = 1234 AND content = 'old content';If the content has changed and no longer matches 'old content', this update will have no effect, so you need to check whether the update took effect and retry if necessary. However, if the database allows the WHERE clause to read from an old snapshot, this statement may not prevent lost updates, because the condition may be true even though another concurrent write is occurring.

Write Skew and Phantoms

Dirty Writes and Lost Updates are not the only type of race conditions.

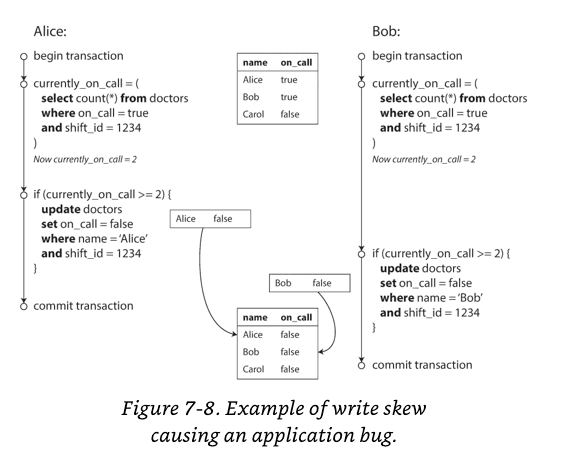

To begin, imagine this example:

You are writing an application for doctors to manage their on-call shifts at a hospital.

The hospital usually tries to have several doctors on call at any one time, but it absolutely must have at least one doctor on call.

Doctors can give up their shifts, provided that at least one colleague remains on call in that shift.

Now imagine that Alice and Bob are the two on-call doctors for a particular shift.

Both are feeling unwell, so they both decide to request leave.

Unfortunately, they happen to click the button to go off call at approximately the same time.

In snapshot isolation, Alice and Bob checks the number of doctors on call, which are 2, so they can proceed the transaction. This violates to having at least one doctor on call.

This anomaly is called write skew. It is neither a dirty write nor a lost update, because the two transactions are updating two different objects.

Write skew can occur if two transactions read the same objects, and then update some of those objects.

To prevent write skews, the options are more restricted:

- Automatically preventing write skew requires true serializable isolation

- If you can’t use a serializable isolation level, the second-best option in this case is probably to explicitly lock the rows that the transaction depends on. In the doctors example, you could write something like the following:

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

SELECT * FROM doctors

WHERE on_call = true

AND shift_id = 1234 FOR UPDATE;

UPDATE doctors

SET on_call = false

WHERE name = 'Alice'

AND shift_id = 1234;

COMMIT;More examples of write skew

Meeting room booking system.

When someone wants to make a booking, you first check for any conflicting bookings (i.e., bookings for the same room with an overlapping time range), and if none are found, you create the meeting

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

-- Check for any existing bookings that overlap with the period of noon-1pm

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM bookings

WHERE room_id = 123 AND

end_time > '2015-01-01 12:00' AND start_time < '2015-01-01 13:00';

-- If the previous query returned zero:

INSERT INTO bookings

(room_id, start_time, end_time, user_id)

VALUES (123, '2015-01-01 12:00', '2015-01-01 13:00', 666);

COMMIT;Claiming a username. On a website where each user has a unique username, two users may try to create accounts with the same username at the same time. You may use a transaction to check whether a name is taken and, if not, create an account with that name.

Preventing double-spending With write skew, it could happen that two spending items are inserted concurrently that together cause the balance to go negative, but that neither transaction notices the other.

Phantoms causing write skew

All of the write skew examples follow a similar pattern:

- A

SELECTquery checks whether some requirement is satisfied by searching for rows that match some search condition - Depending on the result of the first query, the application code decides how to continue

- If the application decides to go ahead, it makes a write (

INSERT,UPDATE, orDELETE) to the database and commits the transaction

In the case of the doctor on call example, the row being modified in step 3 was one of the rows returned in step 1, so we could make the transaction safe and avoid write skew by locking the rows in step 1 (SELECT FOR UPDATE). However, the other three examples are different: they check for the absence of rows matching some search condition, and the write adds a row matching the same condition.

If a write in one transaction changes the result of a search query in another transaction, is called a phantom. Snapshot isolation avoids phantoms in read-only queries, but in read-write transactions like the examples we discussed, phantoms can lead to particularly tricky cases of write skew.

Materializing conflicts

If the problem of phantoms is that there is no object to which we can attach the locks, perhaps we can artificially introduce a lock object into the database?

For example, in the meeting room booking case you could imagine creating a table of time slots and rooms.

Serializability

Serializable isolation is usually regarded as the strongest isolation level. It guarantees that even though transactions may execute in parallel, the end result is the same as if they had executed one at a time, serially, without any concurrency.

But if serializable isolation is so much better than the mess of weak isolation levels, then why isn’t everyone using it?

Actual Serial Execution

The simplest way of avoiding concurrency problems is to remove the concurrency entirely: to execute only one transaction at a time, in serial order, on a single thread.

Even though this seems like an obvious idea, database designers only fairly recently — around 2007 — decided that a single-threaded loop for executing transactions was feasible.

If multi-threaded concurrency was considered essential for getting good performance during the previous 30 years, what changed to make single-threaded execution possible?

- RAM became cheap enough that for many use cases it is now feasible to keep the entire dataset in memory

- Database designers realized that OLTP transactions are usually short and only make a small number of reads and writes.

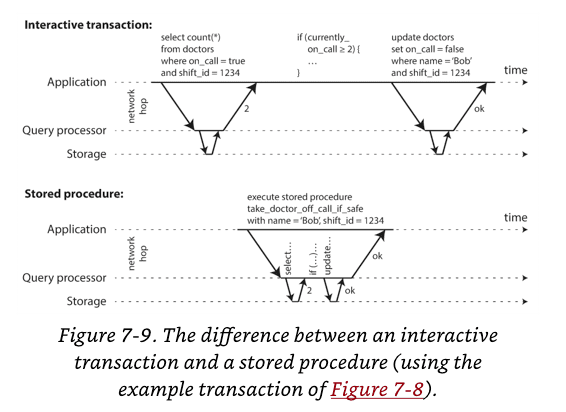

Encapsulating transactions in stored procedures

In the interactive style of transaction (such as a transaction equal to a single network request), a lot of time is spent in network communication between the application and the database. If you were to disallow concurrency in the database and only process one transaction at a time, the throughput would be dreadful because the database would spend most of its time waiting for the application to issue the next query for the current transaction. For this reason, systems with single-threaded serial transaction processing don’t allow interactive multi-statement transactions. Instead, the application must submit the entire transaction code to the database ahead of time, as a stored procedure. Provided that all data required by a transaction is in memory, the stored procedure can execute very fast, without waiting for any network or disk I/O.

Two-Phase Locking (2PL)

In Two-phase locking, several transactions are allowed to concurrently read the same object as long as nobody is writing to it. But as soon as anyone wants to write (modify or delete) an object, exclusive access is required.

- If transaction A has read an object and transaction B wants to write to that object, B must wait until A commits or aborts before it can continue.

- If transaction A has written an object and transaction B wants to read that object, B must wait until A commits or aborts before it can continue. (Reading an old version of the object is not acceptable under 2PL)

The blocking of readers and writers is implemented by having a lock on each object in the database. The lock can either be in shared mode or in exclusive mode.

- If a transaction wants to read an object, it must first acquire the lock in shared mode. Several transactions are allowed to hold the lock in shared mode simultaneously, but if another transaction already has an exclusive exclusive lock on the object, these transactions must wait.

- If a transaction wants to write to an object, it must first acquire the lock in exclusive mode. No other transaction may hold the lock at the same time (either in shared or in exclusive mode), so if there is any existing lock on the object, the transaction must wait.

- After a transaction has acquired the lock, it must continue to hold the lock until the end of the transaction (commit or abort). This is where the name “two-phase” comes from: the first phase (while the transaction is executing) is when the locks are acquired, and the second phase (at the end of the transaction) is when all the locks are released.

Since so many locks are in use, it can happen quite easily that transaction A is stuck waiting for transaction B to release its lock, and vice versa. This situation is called deadlock.

Performance of 2PL

Transaction throughput and response times of queries are significantly worse under two-phase locking than under weak isolation. This is partly due to the overhead of acquiring and releasing all those locks, but more importantly due to reduced concurrency. Also, although deadlocks can happen with the lock-based read committed isolation level, they occur much more frequently under 2PL serializable isolation

Predicate Locks

Predicate lock: Works similarly to the shared/exclusive lock described earlier, but rather than belonging to a particular object (e.g., one row in a table), it belongs to all objects that match some search condition, such as:

SELECT * FROM bookings

WHERE room_id = 123 AND

end_time > '2018-01-01 12:00' AND

start_time < '2018-01-01 13:00';A predicate lock restricts access as follows:

- If transaction A wants to read objects matching some condition, like in that SELECT query, it must acquire a shared-mode predicate lock on the conditions of the query. If another transaction B currently has an exclusive lock on any object matching those conditions, A must wait until B releases its lock before it is allowed to make its query.

- If transaction A wants to insert, update, or delete any object, it must first check whether either the old or the new value matches any existing predicate lock. If there is a matching predicate lock held by transaction B, then A must wait until B has committed or aborted before it can continue.

The key idea here is that a predicate lock applies even to objects that do not yet exist in the database, but which might be added in the future (phantoms).

Index-range locks

Unfortunately, predicate locks do not perform well: if there are many locks by active transactions, checking for matching locks becomes time-consuming.

For that reason, most databases with 2PL actually implement index-range locking (also known as next-key locking), which is a simplified approximation of predicate locking

It’s safe to simplify a predicate by making it match a greater set of objects. For example, if you have a predicate lock for bookings of room 123 between noon and 1 p.m., you can approximate it by locking bookings for room 123 at any time, or you can approximate it by locking all rooms (not just room 123) between noon and 1 p.m.

This provides effective protection against phantoms and write skew. Index-range locks are not as precise as predicate locks would be (they may lock a bigger range of objects than is strictly necessary to maintain serializability), but since they have much lower overheads, they are a good compromise.

Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI)

SSI is fairly new: it was first described in 2008 and is the subject of Michael Cahill’s PhD thesis.

Pessimistic versus optimistic concurrency control

Two-phase locking is a so-called pessimistic concurrency control mechanism: it is based on the principle that if anything might possibly go wrong, it’s better to wait until the situation is safe again before doing anything.

By contrast, serializable snapshot isolation is an optimistic concurrency control technique.

Optimistic in this context means that instead of blocking if something potentially dangerous happens, transactions continue anyway, in the hope that everything will turn out all right.

Optimistic concurrency control is an old idea, and its advantages and disadvantages have been debated for a long time. It performs badly if there is high contention (many transactions trying to access the same objects), as this leads to a high proportion of transactions needing to abort. However, if there is enough spare capacity, and if contention between transactions is not too high, optimistic concurrency control techniques tend to perform better than pessimistic ones.

Decisions based on an outdated premise

In the doctor-on-call example, each transactions is taking an action based on a premise (a fact that was true at the beginning of the transaction, e.g., “There are currently two doctors on call”).

How does the database know if a query result might have changed?

There are two cases to consider:

- Detecting reads of a stale MVCC object version (uncommitted write occurred before the read)

- Detecting writes that affect prior reads (the write occurs after the read)

Detecting stale MVCC reads

When a transaction reads from a consistent snapshot in an MVCC database, it ignores writes that were made by any other transactions that hadn’t yet committed at the time when the snapshot was taken.

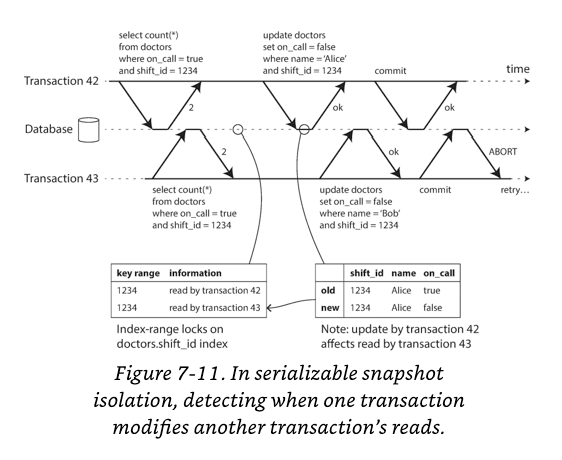

In the diagram below, transaction 43 sees Alice as having on_call = true, because transaction 42 (which modified Alice’s on-call status) is uncommitted. However, by the time transaction 43 wants to commit, transaction 42 has already committed. This means that the write that was ignored when reading from the consistent snapshot has now taken effect, and transaction 43’s premise is no longer true.

In order to prevent this anomaly, the database needs to track when a transaction ignores another transaction’s writes due to MVCC visibility rules. When the transaction wants to commit, the database checks whether any of the ignored writes have now been committed. If so, the transaction must be aborted.

Why wait until committing? Why not abort transaction 43 immediately when the stale read is detected? Well, if transaction 43 was a read-only transaction, it wouldn’t need to be aborted, because there is no risk of write skew.

Detecting writes that affect prior reads

The second case to consider is when another transaction modifies data after it has been read.

In above diagram, transactions 42 and 43 both search for on-call doctors during shift 1234. If there is an index on shift_id, the database can use the index entry 1234 to record the fact that transactions 42 and 43 read this data.

When a transaction writes to the database, it must look in the indexes for any other transactions that have recently read the affected data.

This process is similar to acquiring a write lock on the affected key range, but rather than blocking until the readers have committed, the lock acts as a tripwire: it simply notifies the transactions that the data they read may no longer be up to date.

Performance of SSI

One trade-off is the granularity at which transactions’ reads and writes are tracked.

- If the database keeps track of each transaction’s activity in great detail, it can be precise about which transactions need to abort, but the bookkeeping overhead can become significant.

- Less detailed tracking is faster, but may lead to more transactions being aborted than strictly necessary.

Compared to two-phase locking, the big advantage of serializable snapshot isolation is that one transaction doesn’t need to block waiting for locks held by another transaction.

Compared to serial execution, serializable snapshot isolation is not limited to the throughput of a single CPU core: