Replication

Replication means keeping a copy of the same data on multiple machines that are connected via a network.

All of the difficulty in replication lies in handling changes to replicated data.

Replica: A node that stores a copy of the database

Why do we want replication in the first place?

- Availability: tolerate node failures

- Scalability: process more requests than a single machine can handle

- Latency: placing replicas geographically closer to users

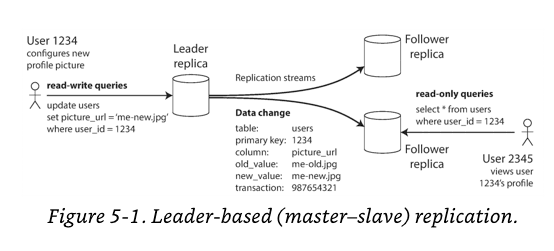

Leaders and Followers

In Leader-based replication, it works as follows:

- One of the replica is designated the leader. All writes requests is sent to this node.

- The other replicas become followers. Whenever the leader writes new data to its local storage, it also sends the data change to all of its followers as a part of

replication logorchange stream. - Read requests cna be queried from either the leader or any of the followers.

It is a built-in feature for many RDBMS + non-relational databases + Message brokers

- PostgreSQL (>= 9.0), MySQL, Oracle Data Guard

- MongoDB, RethinkDB, Espresso

- Kafka, RabbitMQ's highly available queues

Synchronous vs Asynchronous Replication

-

Synchronous: Leader waits until the follower's node is synced with leader- Follower is guaranteed to have an up-to-date copy

- If leader fails, up-to-date data is still available

- If follower fails during request, the write can't be processed, and the leader must block all writes and wait.

- Thus, it is impractical for all followers to be synchronous. Use

semi-synchronousconfiguration more often.

- Thus, it is impractical for all followers to be synchronous. Use

-

Asynchronous: Leader does not wait for the follower's response- Durability is weakened: if the leader fails and writes has not been replicated, the data is lost

- May sound like a bad trade-off, but is nevertheless widely used, especially if there are many followers or if they are geographically distributed

- Durability is weakened: if the leader fails and writes has not been replicated, the data is lost

Setting Up New Followers

How do you ensure that the new follower has an accurate copy of the leader's data?

Naive Solutions

- Copy data files from one node to another? -> data is always in flux, so result might not make any sense

- Make files on disk consistent by locking the database -> go against high availability

Snapshot Solution

- Take a consistent snapshot of the leader's database at some point of time(if possible, without locking the entire database)

- Copy the snapshot to the new follower node

- Follower connects to the leader and requests all data changes since the snapshot. This requires that snapshot is associated with an exact position in the leader's replication log.

Handling Node Outages

How do you achieve high availability with leader-based replication?

Goal: Keep the system as a whole running despite individual node failures.

Follower failure: Catch-up recovery

Each follower keeps a log of the data changes it has received from the leader. If follower crash, recovery is quite easy: from its log, recover until the last successful transaction, and connect to leader for sync.

Leader failure: Failover

Leader failure, a.k.a. is a bit more trickier. Following must be achieved (aka failover):

- One of the followers needs to be promoted to be the new leader

- Clients need to be reconfigured to send writes to the new leader

- Followers need to start consuming data from the new leader

Automatic failover usually consists of the following steps:

- Determining that the leader has failed. Since there is no foolproof way of detecting what has gone wrong, most systems simply use a timeout.

- Choosing a new leader

- Reconfiguring the system to use the new leader

Failover is fraught with things that can go wrong:

- If asynchronous replication is used, the new leader may not have received all the writes from the old leader before it failed.

Split brain: In certain fault scenarios, it could happen that two nodes both believe that they are the leader.- What is the right timeout before the leader is declared dead? Longer timeout means a longer time to recovery, but if timeout is too short, there could be unnecessary failover.

Implementation of Replication Logs

Statement-based replication

In the simplest case, the leader logs every write requests (statement) and sends that statement log to followers. For a relational database, this means that every INSERT, UPDATE, INSERT, or DELETE statement is forwarded.

- Any nondeterministic function, such as

NOW(), orRAND()is likely to generate a different value on each replica. - If statements use an auto-incrementing column, or if they depend on existing data in the database, they must be executed in exactly the same order on each replica. This is limiting when there are multiple concurrently executing transaction.

Workaround is that the leader can replace any nondeterministic function calls with a fixed return value, but there are many edge cases.

Write-ahead log (WAL) shipping

In this case, log is an append-only sequence of bytes containing all writes to the database. The main disadvantage is that the log describes the data on a very low level, and thus replication is closely coupled to the storage engine.

Logical (row-based) log replication

A logical log is usually a sequence of records describing writes to database tables at the granularity of a row. Since a log is decoupled from the storage engine internals, it can more easily be kept backward compatible.

Trigger-based replication

What if you only want to replicate a subset of the data, or want to replicate from one kind of database to another?

A trigger lets you register custom application code, log change to external process, and this applies/replicate the data change. Has greater overhead, and is more prone to bugs and limitations, but can be useful due to its flexibility.

Problems with Replication Lag

Eventual Consistency: All followers will eventually catch up and become consistent with the leader

Replication Lag: The delay between a write happening on the leader and being reflected on a follower

What if replication lag is large?

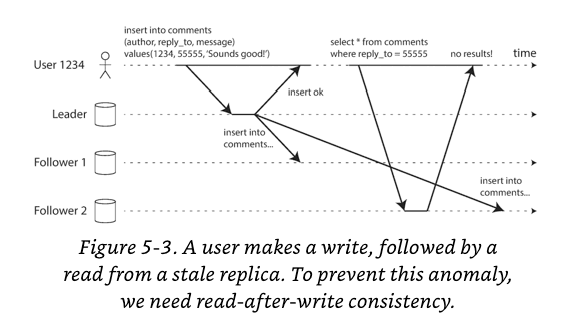

Reading Your Own Writes

In asynchronous replication, if the user views the data shortly after making a write, the data may not be the "new" version.

Read After Write Consistency : guarantee that user will always see any updates made by the user.

Various possible techniques achieve this:

- When reading something that the user may have modified, read it from the leader. How do you know what is modified by yourself? Specify contents, such as user profile.

- If many things in the application are editable by user, the approach is not feasible.

- Track the time of last update, and for one minute after the last update, make all reads from the leader.

- client can remember the timestamp of its most recent write, so if replica is behind the timestamp, read can be handled by other replica.

What if same user is accessing the service from multiple devices?

- Remembering the timestamp of user's last update is difficult, so metadata will need to be centralized

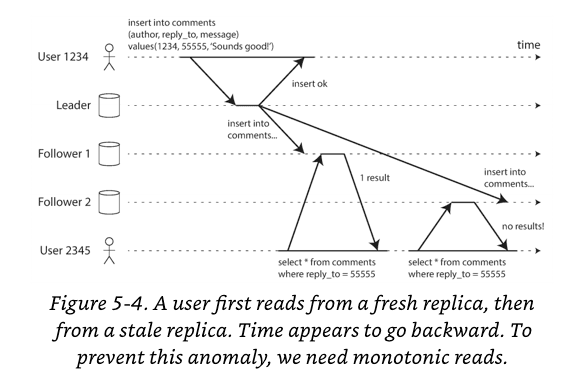

Monotonic Reads

It's possible for a user to see things moving backward in time.

Monotonic Reads: if user makes several reads in sequence, they will not read older data after having previously read newer data.

Consistency strength: eventual < monotonic < strong consistency

This can be achieved by:

- user always make their read from the same replica

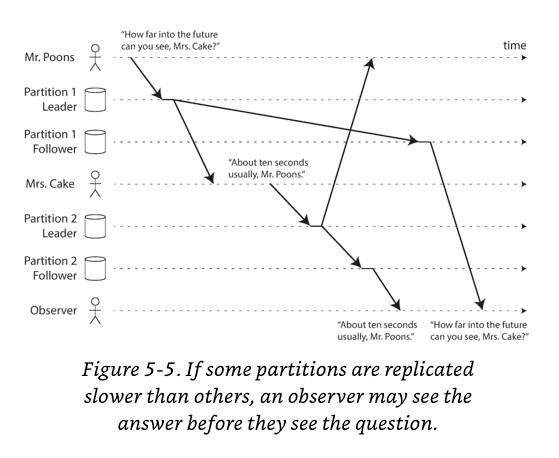

Consistent Prefix Reads

It's possible that there are violations of causality.

Mr.Poons: How far in the future can you see, Mrs.Cake?

Mrs.Cake: About ten seconds usually, Mr.Poons.Currently, there is a causal dependency. If a third person is listening to this conversation through followers, and if messages sent by Mr.Poons have longer replication lag, following could occur.

Mrs.Cake: About ten seconds usually, Mr.Poons.

Mr.Poons: How far in the future can you see, Mrs.Cake?

Consistent Prefix Read: guarantee that if a sequence of writes happens in a certain order, then anyone reading those writes will see them in the same order.

Solutions for Replication Lag

It would be better if application developers didn't have to worry about the subtle replication issues and could just trust their databases to do the right thing. This is why transactions exist, which is discussed in later chapters.

Multi-Leader Replication

Leader-based replication has one major downside: there is only one leader, and all writes must go through it.

Why not have more leaders?

Use Cases for Multi-Leader Replication

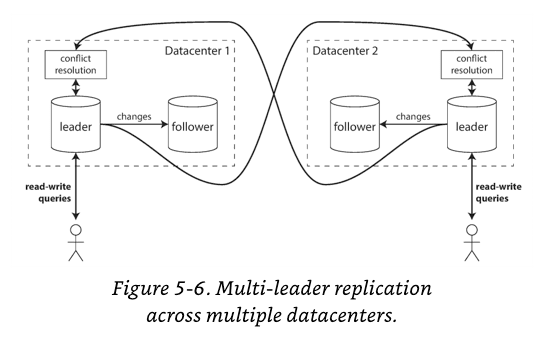

Multi-datacenter Operations

In multi-leader configuration, you can have a a leader in each datacenter.

Comparison with single vs multi leader configuration in a multi datacenter deployment.

| Single | Multi | |

|---|---|---|

| Performance | Latency in writes | Small latency, as write is processed in the local datacenter |

| Tolerance of datacenter outages | Failover can promote a follower in another datacenter | Each datacenter can continue operating independently of others |

| Tolerance of network problems | very sensitive to problems in inter-datacenter link | better in tolerating |

Downside of multi-datacenter operations

- the same data may be concurrently modified in two different datacenters and those write conflicts must be resolved.

- there are configuration pitfalls, such as auto-incrementing keys, trigger, and integrity constraints.

- often considered dangerous territory that should be avoided if possible

Clients with offline operations

If application needs to continue to work while it is disconnected from the internet, multi-leader can be appropriate.

In this case, your device is the leader.

Collaborative Editing

Real-time collaborative editing applications, such as Google Docs can be a good usecase.

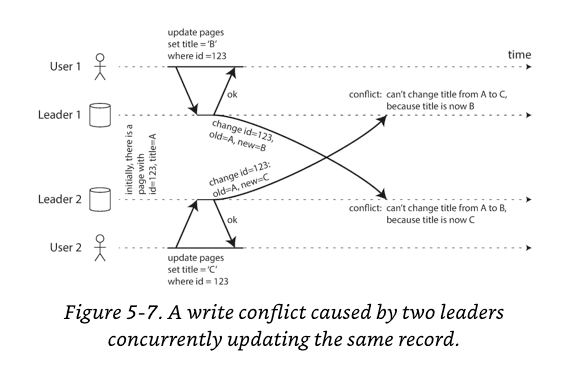

Handling Write Conflicts

The biggest problem is to handle write conflicts.

If changes are asynchronously replicated, a conflict is detected.

The simplest solution is to avoid conflicts.

- Assign the same datacenter, and leader node for a particular user.

Other solution is to eventually converge:

- Give each write a unique Id, and make the last write win (LWW).

Multi-Leader Replication Topologies

Replication Topology: describe the communication paths along which writes are propagated from one node to another.

- all-to-all: most general, some network links may be faster than others

- circular: MySQL's default, write may need to pass several nodes before it reaches all replicas, single point of failure

- star: can be generalized to a tree, write may need to pass several nodes before it reaches all replicas, single point of failure

Leaderless Replication

Allow any replica to directly accept writes from clients, Amazon used it for its in-house Dynamo system.

Writing to the Database When a Node Is Down

In leaderless replication, failover does not exist.

In this diagram, reader may get stale(=outdated) values as responses. To solve this problem, read requests are also sent to several nodes in parallel.

After an unavailable node comes back online, how does it catch up on the writes that it missed?

Read repair and anti-entropy

The replication system should ensure that eventually all the data is copied to every replica.

Read repair: when a client makes a read request from several nodes in parallel, it can detect any stale responses, and writes the newer value back to that replica. This approach works well for the values that are frequently read.

Anti-entropy process: have a background process that constantly looks for differences in data between replicas and copies any missing data from one to another. There could be significant delay before data is copied.

Quorums for Reading and Writing

If there are n replicas, every writes must be confirmed by w nodes, and every read must query at least r nodes, such that w + r > n.

A common choice is to set n as an odd number, and w = (n + 1) / 2, rounded up.

With w + r > n, we can tolerate the system as follows:

- if

w < nwe can still process writes if a node isi unavailable. - if

r < nwe can still process reads if a node is unavailable. - With

n = 3, w = 2, r = 2we can tolerate one unavailable node. - With

n = 5, w = 3, r = 3we can tolerate two unavailable nodes.

Limitations of Quorum Consistency

Even with w + r > n, there are likely to be edge cases where stale values are returned.

- If a sloppy quorum is used, the

wwrites may end up on different nodes than therreads, so there is no longer overlap betweenrandwnodes. - If two writes occur concurrently, it is not clear which one happened first.

- If write succeeded on some replicas but failed on others, and overall succeeded fewer than

wreplicas, subsequent reads may or may not return the value from that write.

Sloppy Quorums and Hinted Handoff

In a very large cluster, it's likely that the client can connect to some database nodes during the network interruption, just not to the nodes that it needs to assemble a quorum for a particular value.

- Is it better to return errors to all requests for which we cannot reach a quorum of w or r nodes?

- Or should we accept writes anyway, and write them to some nodes that are reachable but aren't among the n nodes on which the value usually lives?

Tha latter is the sloppy quorum, which is useful for increasing the write availability.

Detecting Concurrent Writes

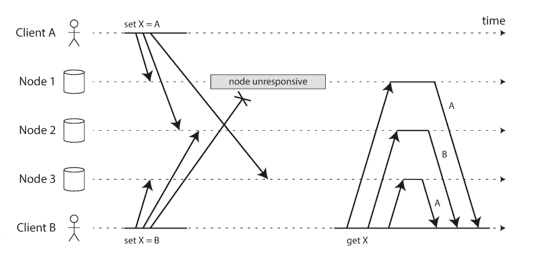

Dynamo-style databases allow several clients to concurrently write to the same key, which means that conflicts will occur even if strict quorums are used.

The problem is that events may arrive in a different order at different nodes, due to variable network delays and partial failures.

For example, the below diagram shows two clients, A and B, simultaneously writing to a key X in a three-node datastore:

- Node 1 receives the write from A, but never receives the write from B due to a transient outage.

- Node 2 first receives the write from A, then the write from B.

- Node 3 first receives the write from B, then the write from A.

How can the system become eventually consistent?

Last write wins (discarding concurrent writes)

We can force an arbitrary order on them. For example, we can attach a timestamp to each write, pick the biggest timestamp as the most “recent,” and discard any writes with an earlier timestamp. LWW achieves the goal of eventual convergence, but at the cost of durability:

The happens-before relationship and concurrency

How do we decide whether two operations are concurrent or not?

Happens Before: another operation B if B knows about A, or depends on A, or builds upon A in some way.Concurrent: if neither happens before the other (i.e., neither knows about the other)

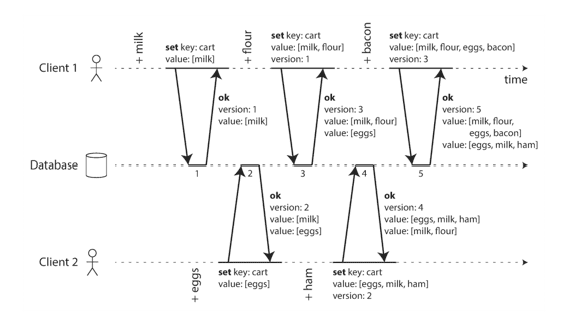

Capturing the happens-before relationship

- Client 1 adds

milkto the cart. This is the first write to that key, so the server successfully stores it and assigns it version 1. The server also echoes the value back to the client, along with the version number. - Client 2 adds

eggsto the cart, not knowing that client 1 concurrently addedmilk(client 2 thought that itseggswere the only item in the cart). The server assigns version 2 to this write, and storeseggsandmilkas two separate values. It then returns both values to the client, along with the version number of 2. - Client 1, oblivious to client 2’s write, wants to add

flourto the cart, so it thinks the current cart contents should be[milk, flour]. It sends this value to the server, along with the version number 1 that the server gave client 1 previously. The server can tell from the version number that the write of[milk, flour]supersedes the prior value of[milk]but that it is concurrent with[eggs]. Thus, the server assigns version 3 to[milk, flour], overwrites the version 1 value[milk], but keeps the version 2 value[eggs]and returns both remaining values to the client. - Similar steps are repeated.

Merging concurrently written values

This algorithm ensures that no data is silently dropped, but it unfortunately requires that the clients do some extra work: if several operations happen concurrently, clients have to clean up afterward by merging the concurrently written values (siblings).

With the example of a shopping cart, a reasonable approach to merging siblings is to just take the union. The two final siblings are [milk, flour, eggs, bacon] and [eggs, milk, ham]. The merged value might be something like [milk, flour, eggs, bacon, ham], without duplicates.

However, to remove things from the cart, union is not suitable. We need some sort of a deletion marker: tombstone.

Version vectors

In the above examples, we kept a version in a single replica. What if there are multiple replicas, without leader? We need to use a version number per replica as well as per key. Each replica increments its own version number when processing a write, and also keeps track of the version numbers it has seen from each of the other replicas.

The collection of version numbers from all the replicas is called a version vector.